Fernando Laposse Takes a Sustainable Approach to Furniture Design

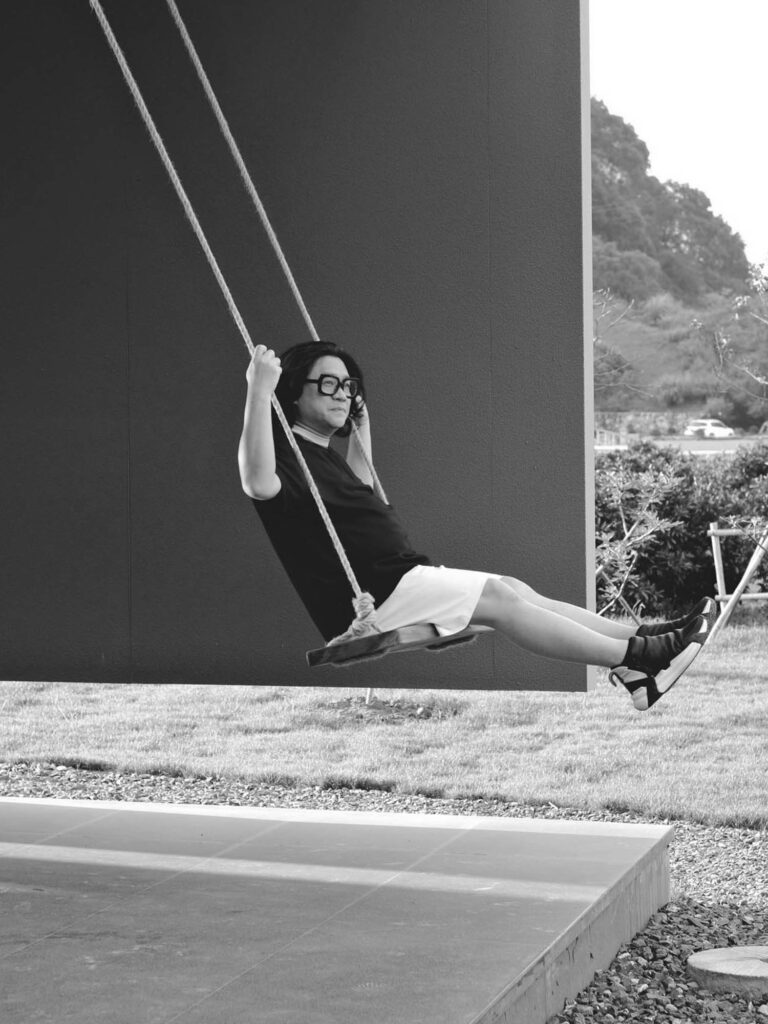

If an exhibition exploring the negative social, economic, and environmental impact of global trade on rural communities sounds like a high-minded lecture you don’t want to attend, think again. Mexican furniture designer Fernando Laposse’s recent one-man show, “Ghosts of Our Towns” at Friedman Benda gallery in New York, was so delightful that its serious themes—the loss of biodiversity, the destruction of rural culture in his homeland—became an energizing riff on engagement, possibility, and the power of collaboration.

Born to Mexican parents in France, raised there and in Mexico, and trained at Central Saint Martins, Laposse is himself a son of globalization. He saw the consequences of international trade agreements and industrialized agricultural methods when he returned to Santo Domingo Tonahuixtla—a tiny indigenous community he’d visited frequently as a child—and found its traditional heirloom corn–growing practices abandoned, its lands eroded, and its inhabitants forced to migrate elsewhere. As the exhibition title suggests, it was fast becoming a ghost town.

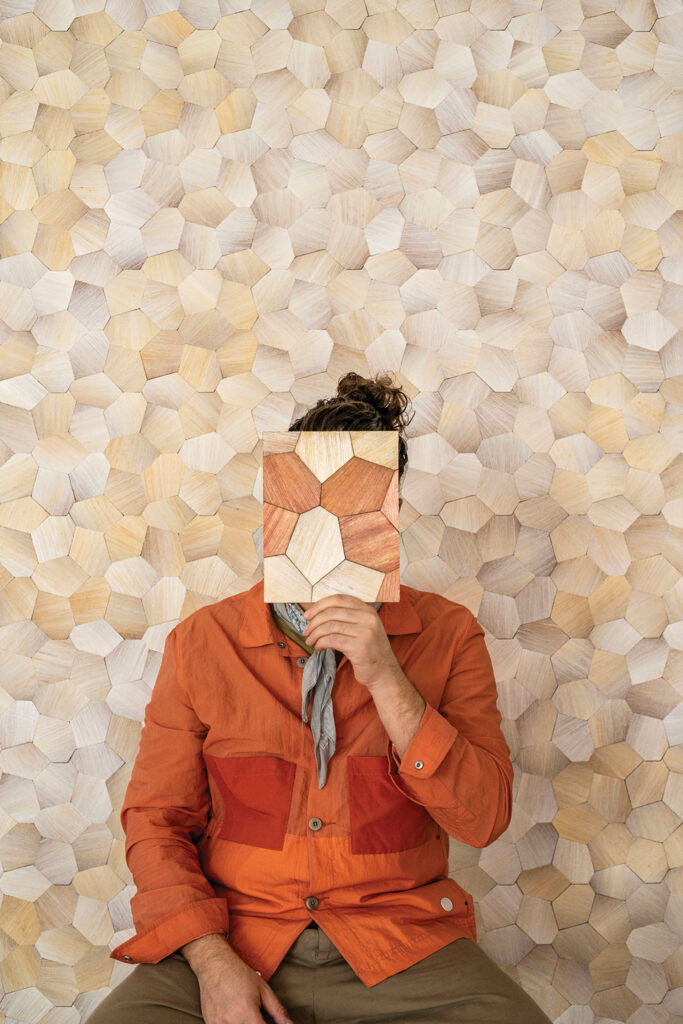

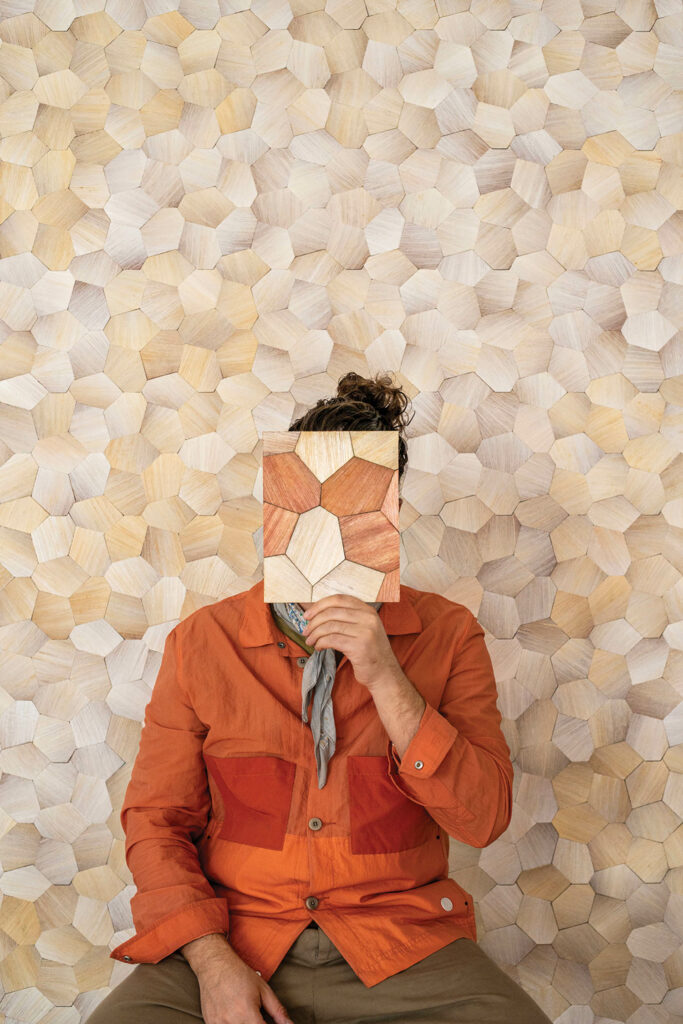

Since 2016, Laposse has collaborated with the townspeople on reestablishing the economic viability of the ancient crop by turning the multicolor husks, regarded as waste, into an innovative product called Totomoxtle, a marquetry veneer that clad some pieces in his show. The sustainable material not only generates new skills, jobs, and income for the community but also helps preserve its social and cultural fabric. Another native plant, the agave, which the village grows in bulk to fight soil erosion, provides fibers for the luxuriant “hair” on some of the other displayed objects. And monumental textile portraits of actual villagers offered a preview of what Laposse will show at Australia’s National Gallery of Victoria Triennial this December. He tells us more.

Fernando Laposse Talks Sustainable Furniture Design

Interior Design: You’re known for your innovative use of humble natural materials such as corn husks and agave leaves. How did that begin?

Fernando Laposse: With the Central Saint Martins foundation course, a year in which I was able to try a bit of everything and really get my hands dirty in the workshops learning a lot of practical skills. We were encouraged to do a project using a material from our own country and I chose loofah. I got to understand the anatomy of the fibrous fruit, navigate its limitations, and “domesticate” it to the point where it could be worked into a piece of furniture. I developed a methodology—filleting it with a knife like a fish, then flattening it—that I still use.

ID: What was your next important material discovery?

FL: Corn husk, which came out of my residency at an Oaxaca foundation started by the artist-activist Francisco Toledo. At the time, there was a lot of pressure to ban GMOs to protect our native corn, but I began to look for ways to create more revenue for the small farmers growing it that didn’t involve the grain itself. I found the answer in the leaves, which are as colorful as the maize kernels. Previously, I’d worked for London designer Bethan Laura Wood, an experience where I learned about marquetry. That led me to treat the dried husks like cardstock, cutting it into small shapes to form a continuous patterned veneer—not too dissimilar to what we’re doing today.

ID: Did that result in your ongoing collaboration with Santo Domingo Tonahuixtla?

FL: Yes. When I first revisited the village, which in many ways had become a ghost town, I was inspired by the 70-year-olds planting agave in the mountains, trying to reverse the erosion. Similarly, we began working on reintroducing ancient varieties of indigenous corn with the help of Mexico’s largest seed bank, using the old ejidos system of communal farming from the 1930’s. We set up a community workshop in the abandoned casa ejidal—the meeting hall where collective decisions were made—to which farmers bring corn husks to be transformed into the final product, including cutting out the shapes with a laser machine. I’d say the bulk of my work over the last nine years has been designing that whole production system. Most of the veneer applications are done in the village workshop, but more complex pieces are finished in my other studio in Mexico City, where we have bigger machines and better electricity!

ID: You presented your Conflict Avocados project, which uses waste skin and pits to make dyes, at this year’s World Around Summit. Tell us about it.

FL: The avocado trade in Mexico—the world’s largest exporter of the fruit, all of which comes from Michoacán—is impacting the country terribly in regard to violence, deforestation, and loss of biodiversity. The textile portraits in the Friedman Benda show, which were made with avocado-dyed cotton, are just a taste of what’s to come.

For the NGV Triennial, we’re currently making a 130-foot-long tapestry telling the story of a Michoacán village that stood up to illegal logging. I’ll also show the original version of Resting Place, a chaise covered in avocado-dyed cotton patches embroidered with guns and knives that commemorates Homero Gómez González, an activist who was murdered for protecting the monarch butterfly’s forest habitat. I want my work to be more than just nice materials I can present at design fairs. I want it to have lasting impact.

read more

DesignWire

Kajsa Willner Says: Don’t Waste Waste, Turn It into Furniture

Kajsa Willner displays her works in “Crafted Potential,” an exhibition that suggests ways waste materials can be used in furniture production.

DesignWire

10 Design Showstoppers from Feria Hábitat València

Feria Hábitat València highlights playful designs by Spanish makers as well as some surprising introductions from firms farther afield.

Projects

30 Sustainable Projects Leading the Way for Green Design

Sustainability is more important than ever and is on its way to becoming a standard in architecture. These projects prove that green design is good for all.

recent stories

DesignWire

10 Questions With… Jessica Helgerson

Jessica Helgerson discusses her new lighting collection with Roll & Hill, some favorite projects, opening a Paris branch of her eponymous firm, and more.

DesignWire

10 Questions With…. Tadashi Kawamata

Get to know Japanese artist Tadashi Kawamata who created a surreal installation for the facade of French design firm Liaigre’s Paris mansion in the fall.

DesignWire

Who’s Who in Design? Read Our Top Interviews of 2023

From seasoned professionals to emerging talents, we’ve rounded up the 10 most-read design interviews of the year, spotlighting industry creatives.